The ruby mines of Myanmar have long been shrouded in both allure and controversy. Nestled in the rugged mountains of Mogok Valley, these mines produce some of the world's most coveted gemstones, their deep red hues symbolizing wealth and power. Yet behind the glittering facade lies a harsh reality—one of backbreaking labor, perilous conditions, and a complex web of economic and political forces. For the miners who toil beneath the earth, the search for rubies is not just a livelihood but a gamble with fate.

Life in the mining towns of Mogok is a world apart from the bustling cities of Myanmar. Here, the rhythm of existence is dictated by the hunt for gems. Miners rise before dawn, their bodies already weary from years of labor. Armed with little more than rudimentary tools—picks, shovels, and sometimes just their bare hands—they descend into narrow, unstable shafts. The air is thick with dust, and the threat of cave-ins looms constantly. "You learn to listen to the earth," says one veteran miner. "When it groans, you run."

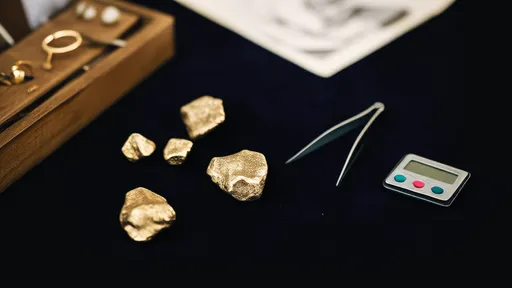

The work is grueling, but the potential rewards keep men returning to the pits day after day. A single high-quality ruby can fetch a life-changing sum, though such discoveries are vanishingly rare. Most miners sift through tons of gravel for mere fragments, earning barely enough to feed their families. The gems they do find often pass through a labyrinth of middlemen before reaching international markets, leaving the miners with only a fraction of their true value. "We dig the stones," one man remarks bitterly, "but others wear them."

Beyond the physical dangers, the mining communities grapple with deeper struggles. Many operations exist in a legal gray area, with informal mining cooperatives operating alongside state-sanctioned enterprises. Corruption is rampant, and clashes over territory or profits frequently turn violent. The military junta's tight control over the industry further complicates matters, as gem revenues are widely believed to fund oppressive regimes. For the miners, politics is a distant concern—survival takes precedence.

Women and children are not spared from this harsh existence. While men dominate the pits, women often work the riverbanks, panning for smaller stones in the silt. Children, some as young as ten, are commonly seen sorting gravel or carrying heavy loads. Education is a luxury few can afford, trapping generations in the cycle of poverty. "My father was a miner, and his father before him," says a teenage boy. "What else is there for me?"

The environmental toll of ruby mining is equally devastating. Forests are cleared to make way for pits, and rivers choked with sediment. Chemical runoff poisons water supplies, leaving communities to face long-term health consequences. Efforts to regulate mining practices have been sporadic at best, with profit consistently trumping sustainability. "The land is dying," laments an elder from a nearby village. "When the rubies are gone, what will be left?"

Despite these challenges, the allure of Mogok's rubies persists. Auction houses in Geneva and Hong Kong still showcase stones from the region, their origins often obscured by layers of paperwork. International buyers rarely glimpse the human cost behind their purchases. Meanwhile, the miners of Mogok continue their relentless search, driven by hope and desperation in equal measure. Their stories, like the rubies they unearth, remain hidden beneath the surface—waiting to be brought into the light.

As global demand for precious gems grows, so too does the urgency to address the realities of Myanmar's ruby trade. Fair-trade initiatives and ethical sourcing programs have emerged, but their impact remains limited in the face of entrenched systems. For now, the miners of Mogok endure, their lives a testament to resilience in one of the world's most unforgiving industries. The rubies may be eternal, but the hands that unearth them are all too human.

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025